By Antonio R. Gargiulo, MD

Dr. Gargiulo is a reproductive endocrinologist and reproductive surgeon at the Center for Infertility and Reproductive Surgery and the Boston Center for Endometriosis at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He is the Medical Director of Robotic Surgery for Brigham Health, and an Associate Professor of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology at Harvard Medical School.

In myomectomy, a procedure where uterine fibroid tumors are removed while preserving the uterus, we must cut into the compressed muscle of the uterus to excise fibroids from their pseudocapsular space. Injury to the muscle of the uterus is often unavoidable, but it must be limited to the absolute minimum necessary. Thus, we consider all options before recommending surgery, selecting only patients with symptomatic tumors that affect their quality of life, or asymptomatic tumors that are very likely to negatively affect the patient’s chances of conceiving or carrying a child.

Challenges of Improving Fertility

Cases where patients are largely asymptomatic and improving fertility is the only goal are particularly delicate. If it is deemed advantageous to remove the tumors, we still must remain cognizant that in doing so, we will injure the uterus, and we may injure the endometrium, the fallopian tubes or the vascular circulation to the ovaries. It’s an enormous task to educate patients so they can make a truly informed decision to proceed with an elective surgery given controversial opinions on this topic. Myomectomy is one of the most difficult gynecological surgeries for the aforementioned reasons (difficulty in establishing the indication for surgery, and difficulty performing uterine microsurgery that produces the least injury to the uterus and the other reproductive organs). There is no regeneration occurring in any reproductive tissue: any cell lost by surgery is lost forever. If we make any area of the uterus unnecessarily thin or fibrotic, then it could rupture or lead to abnormal placentation. The surgeon faces a double challenge with myomectomy: he/she must be both precise (microsurgical) and quick (because of the active bleeding that goes on during this repair). Blood is the sand in the hourglass of myomectomy.

A.

B.

C.

Figure Legend:

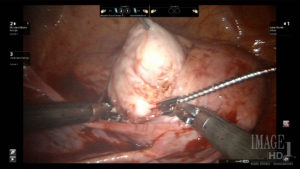

A laser knife assists in the safe excision of myomas from unusual and delicate spaces, such as anterior cervical myomas (A and B) and retroperitoneal myomas (C), due to the absence of lateral thermal spread.

Robotic CO2 Laser Myomectomy

Some major advances in surgical technology have made it easier to perform myomectomy and while preserving fertility. The first one is robotic surgery. This was a particular boon for myomectomy, because the procedure is very suture-intensive, and precise and fast suturing is very difficult to accomplish laparoscopically. Another one is self-anchoring (barbed) sutures. These further reduce uterine bleeding and surgery time.

However, if we want to operate by the tenets of microsurgery, we cannot ignore the fact that conventional robotic cutting instruments (based on electrocautery) have significant lateral thermal spread and will therefore result in the unnecessary loss of precious functional myometrium. Also in this field, technical advances have come to our aid. We have to choose the tool that will produce the least injury to the uterus, and the CO2 laser is that tool.

My current CO2 laser, the Lumenis UltraPulse Duo CO2 laser with FiberLase waveguide, also makes it easier to perform myomectomy while minimizing damage. The key is the ability to excise tissue cleanly and efficiently with a lateral thermal spread of only about 100 microns. The result is decreased loss of functional myometrium (middle layer of the uterus) compared to other technologies that have over 5mm thermal spread (50x more than the CO2 laser). Not many surgeons have adopted laser blades yet, probably because lasers with classic line-of-sight were challenging to use in the past. Laser fibers instead have a very user-friendly profile and can be safely controlled by robotic instruments inside the abdomen. These improvements reduce morbidity, complications, and need for postoperatieve analgesia, while increasing the likelihood that our patients will succeed in spontaneous or assisted reproduction.

The content presented on this page is provided for informational and/or educational purposes. This material represents the views and opinions of its authors and should not be construed as representing or reflecting the official position, views or opinions of the Society of Laparoscopic & Robotic Surgeons. The authors of the work are solely responsible for its content.